The Battenkill River

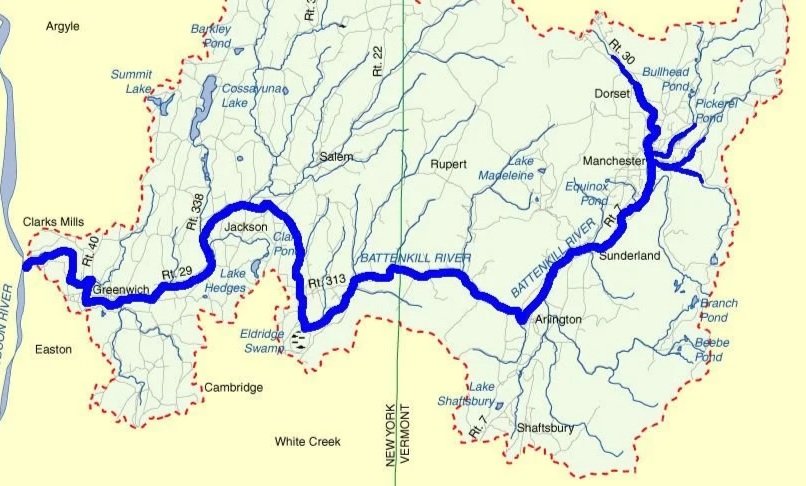

The Battenkill River is one of the most historically and ecologically distinctive trout rivers in the northeastern United States. Flowing roughly 59 miles from the slopes of Vermont into eastern New York before joining the Hoosic River, the Battenkill is best understood not as a single watercourse but as a living system shaped by geology, climate, insects, and centuries of human use.

Its character—clear, deceptively gentle, and exacting—comes directly from its natural history.

The river rises in the southern Green Mountains, draining a landscape of forested hills, pastureland, and glacial soils before turning west through the broad agricultural valleys of Arlington and Manchester. Unlike freestone rivers that tumble steeply through bedrock canyons, the Battenkill flows across glacial till and limestone-influenced soils, producing a moderate gradient and a substrate of gravel, cobble, and sand. This geology creates long riffles, subtle seams, and classic pool-run structure—features that reward careful observation rather than forceful casting.

Hydrologically, the Battenkill is a spring-fed river with relatively stable flows compared to steeper mountain streams. Groundwater inputs moderate temperature swings and help sustain cold, oxygen-rich water through much of the summer, even as surrounding valleys warm. Seasonal snowmelt drives the river’s highest flows in early spring, reshaping gravel beds and refreshing spawning habitat. By midsummer, the river settles into lower, clearer conditions that demand precision and restraint from anglers—and favor trout adapted to efficiency rather than aggression.

Ecologically, the Battenkill supports a self-sustaining population of wild brown trout, with additional populations of brook trout in cooler tributaries and upper reaches. These fish are products of their environment: strong, selective feeders that occupy narrow feeding lanes and rely heavily on drifting insects rather than chasing prey. Growth rates tend to be slow but steady, producing fish known more for wariness and longevity than sheer size.

The river’s entomology is central to its identity. Classic mayfly hatches—most notably Hendrickson mayfly and Blue-winged olive—have shaped both local trout behavior and the evolution of American dry-fly fishing. Caddisflies, stoneflies, and midges fill the calendar before and after the marquee events, creating a near-constant, if often subtle, food supply. These insects emerge in response to light, temperature, and flow conditions, reinforcing the Battenkill’s reputation as a river that rewards timing and understanding over persistence.

Human history has also left a light but lasting imprint. The Battenkill powered early mills and supported agricultural communities long before it became a destination for anglers. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it had entered the canon of American fly fishing, admired for its elegance and difficulty. Unlike rivers engineered for maximum fish density, the Battenkill largely retained its natural form. Conservation efforts in the late 20th century emphasized habitat protection, catch-and-release ethics, and respect for private land, helping preserve the river’s understated character.

Today, the Battenkill stands as a counterpoint to more heavily managed trout waters. Its natural history explains why success here is measured less in numbers than in moments: a single rising trout, a correct drift, a hatch observed rather than forced. The river’s geology slows it, its hydrology steadies it, its insects discipline its fish, and its history has taught generations of anglers patience. Those same forces continue to shape the Battenkill, season after season, as a river that teaches attentiveness as much as it offers opportunity.